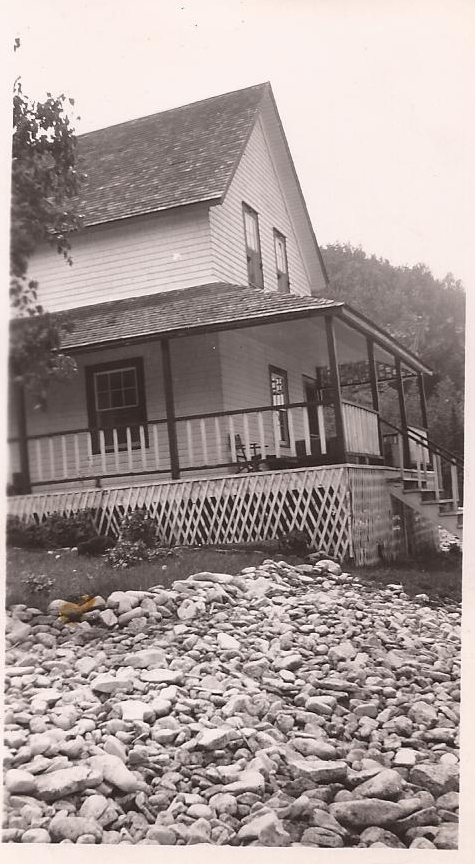

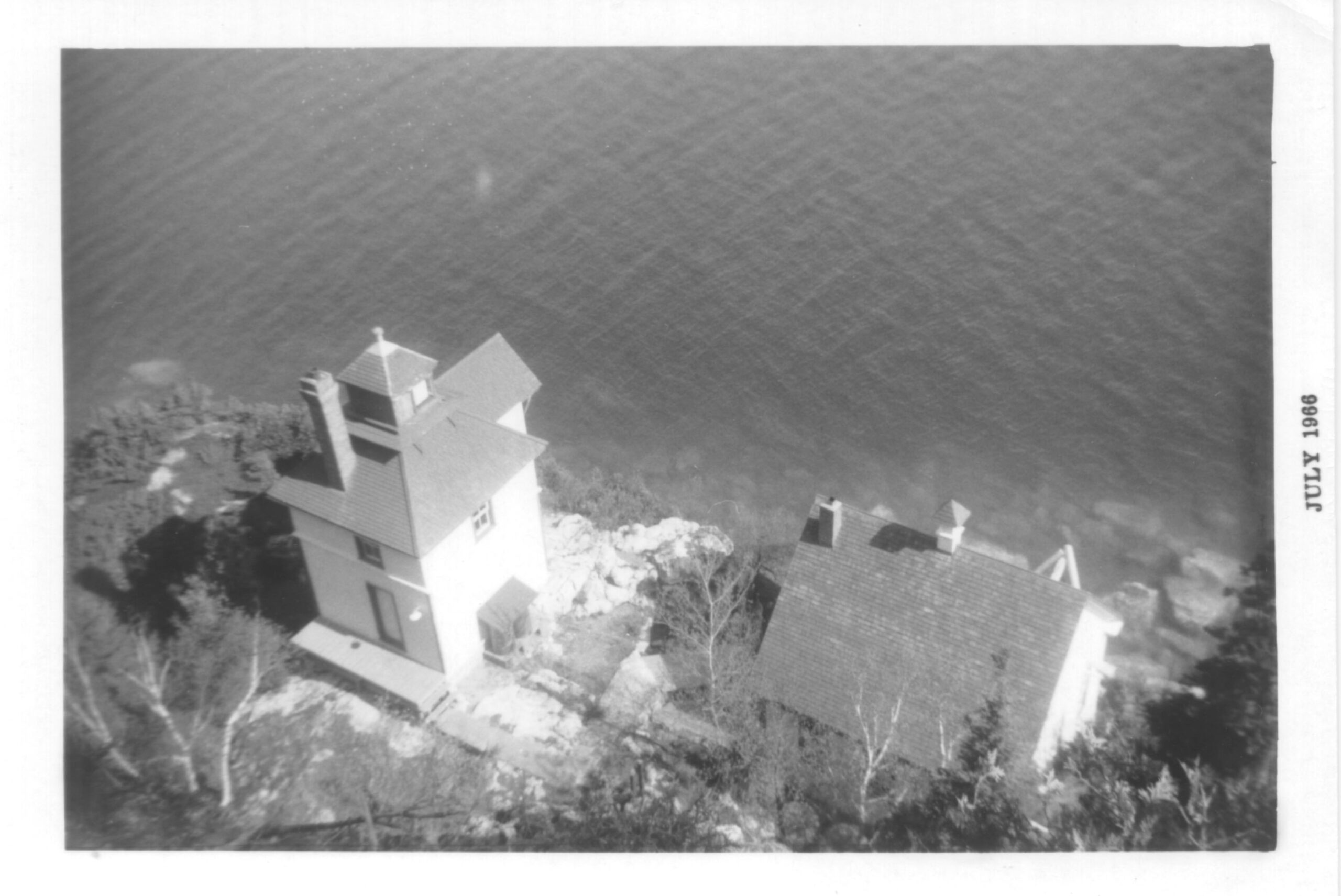

Courtesy of the Coultis Family Collection

THE HISTORY OF GREAT LAKES LIGHTHOUSES AND THE FLOWERPOT ISLAND LIGHTSTATION

Before modern day marine charts, weather forecasting, radar and GPS, experiencing a storm on the Great Lakes was to be avoided as much as possible. Great Lakes captains did not have a wide ocean with the option of running before a storm. They had to navigate through narrow, uncharted waters with no navigational aids, no matter the weather. They relied on memory and instinct, navigating ‘by ear, by nose and by God’. Great Lakes sailors would tell stories about smelling the cedar and pine trees from land they couldn’t see, which often meant they were too close.

When Canada opened up to European settlement in the 1800’s, transportation by ship was the most practical and often the only way to carry goods and people on the upper Great Lakes. In 1818 Admiral Henry Wolsey Bayfield was hired to chart the islands and shorelines of Georgian Bay and the North Channel. It took four years to complete but there still remained hundreds of unmarked shoals just below the water’s surface.

It was clear that the upper lakes had to be better lit. While there were lighthouses on the lower Great Lakes, as of November 1854 there were no lighthouses above Goderich on Lake Huron. As a result the largest lighthouse building program ever seen in Canada began in 1855.

The first wave of this lighthouse building program featured the construction of six “imperial” stone towers. A beautiful example of an imperial tower today is located on nearby Cove Island. The final cost to build the six imperial towers was so prohibitive that no more were ever built on Lake Huron/Georgian Bay.

Following Confederation in 1867 a second wave of lighthouse building began. In this wave lighthouses and lantern rooms were built of wood which was cheap and plentiful. These lighthouses were built at a fraction of the cost of the imperial towers. These economical lights used simple reflectors and inexpensive fuels such as kerosene. Many of the lighthouses built in this second wave were in the Manitoulin Island/North Shore Channel area.

By the 1880’s the Bruce Saugeen Peninsula was well settled and a third wave of lighthouse building saw lighthouses built at the entrance to Tobermory’s Big Tub Harbour, and on Cabot Head and Flowerpot Island. Steam fog alarms were also introduced at this time.

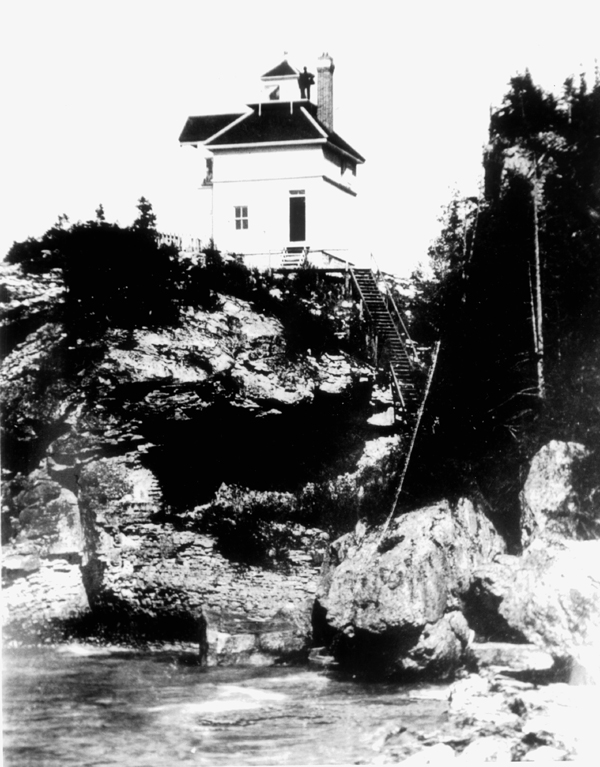

It was during this third wave that tapering polygon towers became popular. These buildings were strong, durable, attractive and unique – such as the Big Tub Lighthouse in Tobermory. The lighthouse design of a frame dwelling with a short tower on the roof was also developed in this third wave. As the height of a tower varied according to need and topography, a tower built on a high cliff like the one on Flowerpot Island, was shorter than usual and even cheaper to build.

This was the final wave of lighthouse building on the Great Lakes. The most important lighthouses had been built.

The lighthouse built on Castle Bluff on the north easterly corner of Flowerpot Island was a square wooden two-storey keeper’s cottage (16’x16’x16’) with a short, wooden tower on the roof. From a height of 33 meters (104 feet) above the water, the fixed white light was visible for 22.4 km (14 miles). This design and setting created a dramatic and beautiful landmark. A fog alarm and plant was established on the same bluff in 1909, replacing earlier, less effective bells and hand-held horns.

The original lighthouse tower was demolished, set on fire and pushed from the cliff in 1969 after being replaced by the current steel tower. The original fog plant was torn down at the same time and a new plant was built on the foundation of the original lighthouse. The fog horn was decommissioned in 1995, but the building still stands. An observation deck was erected on the foundation of the original fog plant.

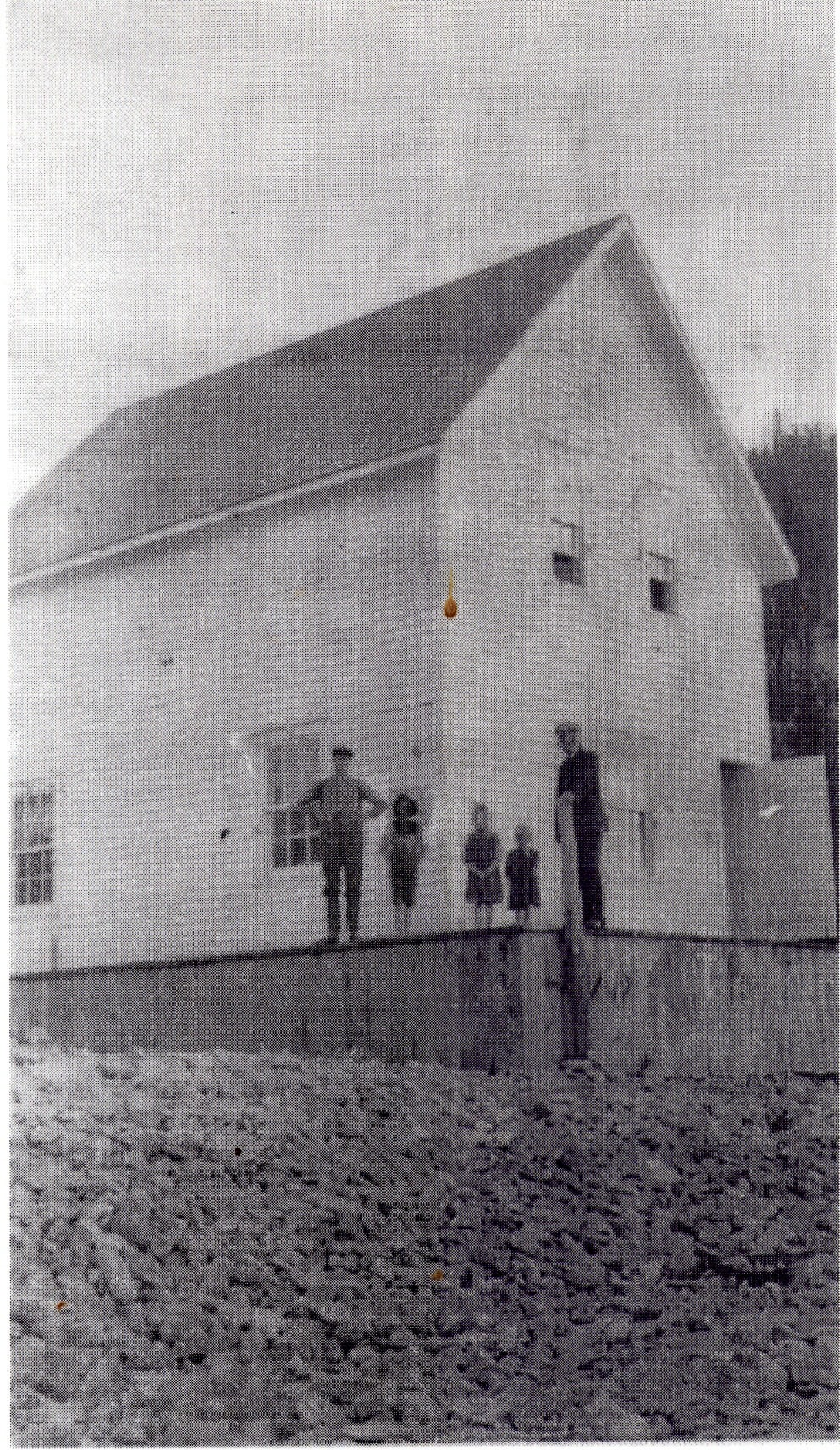

On the cobble stone beach nearby, a two-storey ‘four-square’ keeper’s house was built in 1901. In 1959 a modern, chief lightkeeper’s ‘bungalow’ home was built nearby. The boathouse/workshop was erected in 1963 replacing an older wooden structure. At the water edge the remains of a dock, which was destroyed in a fierce winter storm in 1987, can be seen. As the Lightstation was to be fully automated and unmanned at the end of that season, the dock was never replaced.

The original lamp used at Flowerpot (a double flat-wick and then a circular-wick Aladdin lamp) was fuelled by coal oil or kerosene into the 1960’s. With the arrival of diesel generators, the light was converted and the houses and workshop now had electricity. Eventually electrical power was provided by an underwater cable originating in Tobermory. This cable was hard to maintain and was finally disconnected in 2012. That same year solar panels were installed. With the conversion to solar power, the original fixed white light that had marked Flowerpot Island since 1897 was changed to a flashing white light. The original 4th order Fresnel Lens from the Flowerpot Island Lightstation is on display at the Parks Canada Visitor Centre in Tobermory.

Changes in the economy of the area came as the 20th century progressed. By World War I, the many ships that once plied the waters of Georgian Bay were rarely seen. The passenger and freight trade declined with the building of new roads. Following World War II economic and social change altered lighthouse life. Radio beacons were added at key stations such as Cove Island and diesel generators were installed, producing electricity for the navigational light and the buildings. Life for lightkeepers and their families was getting easier.

With the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 sea-going ships could now sail all the way from the Atlantic Ocean to Thunder Bay or Duluth on Lake Superior. Ships no longer had to enter Georgian Bay. This was the beginning of the end for many lighthouses. In 1962 the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) was formed and was given the job of automating lightstations. Under their care lighthouses continued to be upgraded and advanced technologies were introduced. These improvements were followed by de-staffing and for some lightstations, destruction. While new technology and automation made the lightkeeper’s lives easier, they also sounded the death knell for lightstations on the Great Lakes.

The Flowerpot Island Lightstation’s last keeper John Freethy, locked the door and left the station for the final time at the close of the 1987 shipping season. The station sat empty and neglected for nine years and was likely on the list for removal, when in 1995 a group of dedicated volunteers received permission from the CCG to preserve, repair, restore and present the Flowerpot Island lightstation as a ‘living’ example of the fast disappearing, much-romanced and almost forgotten era of lightkeeping. The Friends of the Bruce Parks Association has a formal licence with Parks Canada, and is responsible for the upkeep, maintenance and showcasing of the remaining buildings on site. The first licence was granted through the Canadian Coast Guard in 1995, and since that time, The Friends has undertaken numerous projects to preserve and protect this important part of Canadian and Great Lakes history.

Occasional witnesses to marine disaster, heroic rescue and unpredictable weather, the Lightkeepers and their families lived lives of hard work in isolation from April to December over the 90 years this station was manned.

The final fate of many Canadian great lakes and coastal lighthouses remains undecided. In spite of attempts to find new purposes for these lighthouses, many have been destroyed or left to decay. Each time that happens a piece of our marine heritage disappears. While the original lighthouse at Flowerpot is long gone, the remaining station buildings are still standing and full of life thanks to the work of the many volunteers and supporters of The Friends.

Courtesy of the Coultis Family Collection